Howard Pyle to Margaret Churchman Painter Pyle (his mother), February 28, 1878

Sunday, February 28, 2010

February 28, 1878

"I hope your patience has not entirely given out at my somewhat lengthened delay in writing. I will not attempt to offer any excuse as I deserve none but will simply throw myself at your mercy with the promise of doing or trying to do better in future."

Friday, February 26, 2010

Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute, 1896

"Howard Pyle, the well-known and deservedly popular draughtsman, has a class at the Drexel Institute, in Philadelphia, that is unique in its way. It differs entirely from the ordinary classes in composition, in that the pupils are kept constantly at work on one or two subjects during the entire term, so that they modify their original drawing many times before it becomes a finished piece of work. Mr. Pyle selects these subjects, and the first step consists in the pupil's execution of the idea in a charcoal sketch. This is submitted to the teacher, who critcises it and hands it back for overhauling. The finished illustration is made in black and white oil. Not only do the highest-grade students at the institute take the course, but Mr. Pyle's class every Saturday is attended by a number of pupils from other schools, as well as by several of those who are already known as illustrators."

New York Times, January 14, 1896

A Howard Pyle Bookmark

I plan to write more in depth about Howard Pyle's involvement with To Have and To Hold, the novel by Mary Johnston, but until then, take a look at this odd scrap of Pylean ephemera...

It's a promotional bookmark which Pyle executed in its entirety (and by that I mean he drew the picture and did the hand-lettering and the border). The portrait is in charcoal and it appears in the background of a 1902 photograph of Pyle taken by his student and sometime photographer, Arthur Ernst Becher (1877-1960). It was initially published in Art Interchange for January 1903.

Becher, by the way, was a friend of Edward Steichen from their days in Milwaukee, and his photographs were shown in the first exhibition of the Photo-Secession (1902) and in Alfred Stieglitz's Camera-Work (October 1903).

And there's certainly something Steichenesque about this Pyle portrait - but perhaps I'm being superficial if it calls to mind Steichen's photo of Rodin: an artist in his studio (presumably) with an example of his work ethereally floating in the background - sort of like those "spirit" photos championed by Arthur Conan Doyle where an image of a dead loved one hovers around the portrait of a living person. Granted, this photograph of Pyle lacks the "mystery" and "atmosphere" of Steichen's Rodin, but still...

It's a promotional bookmark which Pyle executed in its entirety (and by that I mean he drew the picture and did the hand-lettering and the border). The portrait is in charcoal and it appears in the background of a 1902 photograph of Pyle taken by his student and sometime photographer, Arthur Ernst Becher (1877-1960). It was initially published in Art Interchange for January 1903.

Becher, by the way, was a friend of Edward Steichen from their days in Milwaukee, and his photographs were shown in the first exhibition of the Photo-Secession (1902) and in Alfred Stieglitz's Camera-Work (October 1903).

And there's certainly something Steichenesque about this Pyle portrait - but perhaps I'm being superficial if it calls to mind Steichen's photo of Rodin: an artist in his studio (presumably) with an example of his work ethereally floating in the background - sort of like those "spirit" photos championed by Arthur Conan Doyle where an image of a dead loved one hovers around the portrait of a living person. Granted, this photograph of Pyle lacks the "mystery" and "atmosphere" of Steichen's Rodin, but still...

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

“The Parting of My Little Boy”

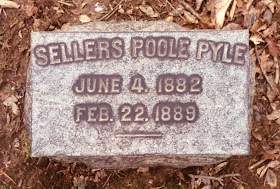

No tragedy in Howard Pyle’s life could ever compare with the death of his son Sellers. The surrounding circumstances only made it more sad. He briefly outlined what happened in a letter I quoted, but here is some more...

No tragedy in Howard Pyle’s life could ever compare with the death of his son Sellers. The surrounding circumstances only made it more sad. He briefly outlined what happened in a letter I quoted, but here is some more...Pyle’s journey to the West Indies was his first trip out of the country (with the probable exception of some Canadian jaunts in 1877). Jamaica was only supposed to be one stop on Pyle’s two-month-long itinerary: he also planned to visit Panama, the Bahamas, and other locales associated with his “Buccaneer heroes” in order to gather material for a couple of Harper’s Monthly articles and for a novel which he hoped would be his magnum opus. His wife, Anne, about nine weeks pregnant with their third child, would accompany him. Their two children would stay in Wilmington: Phoebe, 2, at home with Anne’s mother, and Sellers, 6, with his aunt (and Howard’s sister) Katharine Pyle, at the house she shared with her father at 802 Franklin Street.

Howard and Anne sailed from New York on February 9, 1889, on the Atlas Line steamship Ailsa. The voyage to Kingston took about a week and Pyle recorded his first impressions of their arrival in “Jamaica, New and Old” (Harper's Monthly, January 1890):

It was all like a dream, for there are times when the real and the unreal interweave so closely that it is hard to unravel the one from the other. Mostly gratification is the unfortunate part of anticipation; it is such a gross and tasteless fruit to be the outcrop of so pretty a flower; but that vision of the south coast of Jamaica, so long looked forward to, was at once so full of the lovely changes of afternoon and evening and moonlit night, and so full of suggestions of the romantic glamour of the past and by-gone life, that the bright threads of fancy and the duller strands of fact interwove themselves into such a motley woof that it was hard indeed to separate the one from the other.Although Pyle’s article goes on to refer to Anne, it gives no hint of the awful way their plans changed.

It was almost yesterday that shivered under a heavy overcoat, with a bleak sky above and a sea of ice below; to-day floated upon the rise and fall of the great ground-swell of a tropic sea, flashing into spray under a humming trade-wind that set the feathery cocoa-palms and the ragged banana leaves upon the distant shore to tossing and swaying. Flying-fish shot like silver sparks, with a flash and gleam from the water to the right and the left, skimmed arrow-like across the heaving valleys of the waves, and disappeared far away with another flash and gleam.

Sellers Pyle died on the morning of February 22 and a telegram must have been sent to Jamaica almost immediately. In his Pyle biography, Henry Pitz wrote, “There was a desperate time of trying to find transportation back home and a wait of many days for a steamer sailing. They reached home long after the funeral.”

But I think Pitz was misinformed: Every Evening of February 23 stated, “The body of the boy was placed in a vault in the Wilmington and Brandywine cemetery to await the arrival of the bereaved parents,” and according to the “Marine Intelligence” of the New York Times, on February 25 the steamship Dorian - with the Pyles aboard - sailed from Morant Bay and arrived in New York on the evening of March 4. The Pyles may have spent the night in quarantine on the boat, but surely they arrived home by the following day, which also happened to be Howard’s 36th birthday.

Surprisingly, after only a week in Wilmington, Pyle returned alone to Jamaica to finish his work. He confined his travels and resultant two-part article solely to the island, however, and he never wrote a novel specific to the area.

Pyle’s leaving home so soon may seem cold-hearted, but his Swedenborgian faith had helped him find solace in a “firm and unfailing belief in a future life” - as well as in writing and drawing and painting.

“I have tried not to let my troubles interfere with my life’s work and ways and think I may say that I have pretty well succeeded,” he explained to Edmund Clarence Stedman. He added, “There are many sad things in this world but few that are unhappy excepting what we make for ourselves.”

And as time wore on, Pyle became more and more convinced that “the bitter delight of a keen and poignant agony” which Sellers’ death represented was necessary to make his own life complete: he saw it as “an agony that has dissolved much - almost all of the poison flesh leaving only a thin membrane to hide from the eyes the brighter light of a life beyond.” As he put it to W. D. Howells (after the publication of The Garden Behind the Moon, which he dedicated to Sellers), “Death is so thin a crust of circumstance that I can feel his heart beat just on the other side.”

Monday, February 22, 2010

February 22, 1889

“In the midst of a most charming trip my wife and I received a cablegram telling us that our little boy - a noble little fellow of six years old had died of membranous croup after only a few hours of sickness. He was our only son and, apart from parental prejudice, was I may say a child of deep mind and noble generosity of character.”

Howard Pyle to Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen, April 13, 1889

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Lost Pylean Ephemera, 1900

Who knows how many unidentified pieces of Pylean ephemera are still out there. For instance, this 1900 advertising booklet for Houghton, Mifflin and Company, which managed to miss both bibliographies. It is uncredited, but Pyle's distinctive hand-lettering gives it away.

February 21, 1885

Illustrators, have you ever received a letter from an admirer who complimented your work and then asked you to send them one of your originals? I recall my father receiving such a letter, which implied that his gift would somehow cure a child's illness. That may be so, but it's hard not to be cynical about these things. Here's how Howard Pyle deflected a request in a letter written 125 years ago today:

In answer to your request for one of my drawings (that, as I take it, being the matter intended in your letter) I am compelled to say that I can hardly take the time to make you such a drawing as the “Lowland Brook” which is the work not of a minute, but a day.Pyle painted "The Lowland Brook" in the fall of 1880, probably beginning it in October on location in the Poconos, then finishing it back in his studio at his parents' house at 714 West Street in Wilmington. It was one of several illustrations for his article, "Autumn Sketches in the Pennsylvania Highlands," published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine for December 1881. The 3.7 x 5.2" engraving was by John Hellawell. Please pardon the printing flaw!

Maybe I may sometime send you a rough sketch if I happen at any time to have one by me, but hardly such a drawing as that...

Thursday, February 18, 2010

February 18, 1892

"The temptation to talk is great but it is so dangerous to formulate thoughts into words. So formulated they become such hard stones of doctrines; such ready weapons to kill the prophets withal."

Howard Pyle to William Dean Howells, February 18, 1892

Monday, February 15, 2010

Presidents Day

Howard Pyle was on friendly terms with three presidents - or, more precisely, two presidents and one future president. The future president was Woodrow Wilson, with whom Pyle carried on a spirited correspondence while collaborating on two projects in 1895-96 and 1900-01. Pyle also knew - if only slightly - William Howard Taft and even wrote some bona fide propaganda for Taft’s 1908 campaign against William Jennings Bryan. But, above all, Pyle was closest to Theodore Roosevelt. And he certainly could lay it on thick sometimes...

If I may write so intimately, I would like to say that it [is] my strong and personal belief that you will stand forth in history as one of the very greatest of our presidents, and it is a matter of pride and joy to me to think that one whom I believe I may regard as a friend should be destined to descend into the future as so dominant and so inspiring a figure. (Howard Pyle to Theodore Roosevelt, September 11, 1907)The admiration went both ways, however, and in honor of Presidents Day, here are some things Roosevelt said to or about Pyle:

This note introduces a particular friend of mine, Mr. Howard Pyle, the writer. He is a first-class fellow in every way and I commend him to your courtesy. (Letter to Captain W. H. Brownson, June 11, 1903)I’ve often wondered what Pyle would have made of the three-way presidential race of 1912 which pitted Taft, Roosevelt, and Wilson against each other. As Pyle was a lifelong Republican (though there’s a chance he turned Mugwump and voted for Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, in 1884), I doubt he would have considered voting for Wilson. And he believed in Taft because he thought Taft would “[carry] forward the work which [Roosevelt had] so magnificently begun to an equally magnificent fulfillment” (Pyle to Taft, November 5, 1908) - something that Taft didn’t really do, after all. So I think Pyle’s idolatry of Roosevelt (and his somewhat progressive tendencies) would have trumped party loyalty, and he would have become a Bull Mooser and followed Roosevelt wherever he went.

You can hardly imagine, my dear fellow, how much I prize your good opinion, and how loath I should be to forfeit it. (Letter to Howard Pyle, July 5, 1904)

One of the very best men I know anywhere, one of the pleasantest companions, stanchest friends, and best citizens, is Mr. Howard Pyle, the artist.... he is as good a man as there is in the country. (Letter to Gifford Pinchot, September 9, 1907)

One of the pleasantest features of our time in Washington has been the friendship of you and dear Mrs. Pyle.

(Letter to Howard Pyle, February 19, 1909)

Exhibit "T"

I don't necessarily want to see Howard Pyle's original illustrations in pristine condition, since the annotations that often appear on them can help shed light on his process. Above is an initial letter "T" for "How the Princess's Pride Was Broken," the twenty-first story (of 24) in his book The Wonder Clock (Harper and Brothers, 1888). He drew it with India ink on a 2.75 x 4.5" piece of Bristol board, glued on a little protective flap (made from a scrap of writing paper, watermarked "[crown] Royal Irish Linen / Marcus Ward / & Co") so it wouldn't get scuffed or too grubby, then labeled both flap and art with purple ink. A staffer in the Harper Art Department probably penciled in "1 1/4 in wide" (the size of the reproduction) and "3-59495 / May 20" (possibly an inventory number and the processing date).

Pyle delivered this "T" along with several other letters on May 16, 1887, and as he delivered the previous batch on May 10, he must have drawn this one between those two dates. So far, this is the only initial letter from the book that I've been able to inspect up close, but I gather he prepared all of them in more or less the same way.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

“St. Valentine’s Day” by Howard Pyle

In his advanced Illustration Class at the Drexel Institute, Howard Pyle occasionally assigned seasonal topics to his pupils with the aim of submitting the best examples to art editors of leading periodicals. Pyle sometimes provided text to go along with or perhaps to inspire his students’ illustrations, and so we have his observations on “Decoration Day” (illustrated by Sophie B. Steel), a Halloween playlet called “The Priest and the Piper” (with a picture by Sarah S. Stilwell), and, apropos of today, “St. Valentine’s Day,” printed in Harper’s Weekly for February 19, 1898, and featuring a double-page spread by Anne Abercrombie Mhoon.

I need to dig up more on Miss Mhoon, who studied with Pyle for about five years and who Pyle must have considered one of his stronger pupils: in spring 1897 she and Bertha Corson Day spent two weeks working in his Wilmington studio; her work was shown in several exhibitions of the Pyle-directed School of Illustration; Pyle featured two of her pictures in his article, “A Small School of Art” (Harper’s Weekly, July 17, 1897); and in 1898 she was one of ten students awarded a scholarship to the first Summer School of Illustration at Chadd’s Ford. If what I’ve learned is accurate, Mhoon was born June 6, 1876, in Mississippi, and died January 2, 1962. She married Hugh McDowell Neely (1874-1925) in Philadelphia in 1906 and had at least one child, named Hugh (1907-1937). All three are buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

“St. Valentine’s Day in New England” by Anne Abercrombie Mhoon (1897)

ST. VALENTINE’S DAY

by Howard Pyle

St. Valentine’s Day in the old times possessed a popular significance that we of these degenerate days of filigree paper and printed rhymes can hardly appreciate. Popular tradition had it that the birds mated upon the good bishop’s natal day, apropos of which Old Drayton, in Shakespeare’s time, writing a verse to his “Valentine,” begins his pastoral thus:

Following these supposed habits of the feathered creatures, it became by-and-by a custom in the generation or so following for the men and women of that day to choose each his or her Valentine, to whom he or she was supposed to remain mated for the rest of the year. The gentleman generally entered into the compact with a poetic effusion and a gift, of more or less value, to the lady of his choice, and for the twelvemonth following he was supposed to devote himself exclusively to his chosen mate.

Usually the element of accident entered not a little into the choosing of the Valentine, for the first man and the first woman who met in the morning were supposed to remain Valentines and mated for the year to follow.

As witness to this, Gay, writing early in the eighteenth century, and beginning with the same theme that inspired Old Drayton -

Once, mounting to the Olympian altitude of the gossip of White Hall, he tells us, apropos of Miss Stuart (afterward Duchess of Richmond), that “The Duke of York being her Valentine, did give her a jewel of about £800; and my Lord Mandeville, her Valentine this year, a ring of about £300.” Descending thence to the platitudes of his own private affairs, the good gentleman tells us very soberly that “I am also this year my wife’s Valentine, and it will cost me £5”; and adds, naïvely, “but that I must have laid out if we had not been Valentines.”

In another entry in his Journal he tells us how his wife hid her eyes lest she should see the masons working about the house, and so should miss choosing her proper Valentine; and in another place he informs us that “My wife, hearing Mr. Moore’s voice in my dressing-chamber, got herself ready, and came down and challenged him for her Valentine.”

From all of which we of these days may catch a certain remote notion of the importance of St. Valentine’s day in those far-distant old times so long passed away and gone.

As illustrating the importance of this one-time notable feast-day, Miss Mhoon has given a pictured image of the transplantation of the custom of the time into Puritan New England of, say, the year 1655.

We know what strong testimony the Puritans bore against the puddings and the “meat pies” (probably the mince pie of our day), and all the jocularities of the old Christmas season, and we also know that they made a point of studiously ignoring the anniversary of the King’s birthday. It is altogether likely they would look with even less favor upon the suggestive levities of Valentine’s day.

The somewhat seedy Cavalier, who is doubtless offering the Puritan maiden an effusion in these, in which dove is made to rhyme with love, and eyes with skies, and dart with heart, has perhaps been spending the whole long winter in the dull, cold little settlement for the sake of escaping, let us say, from the pressure of his debts at home. One can imagine how greatly a man of his parts must have wasted in such surroundings as the picture indicates. As for the Puritan maiden, either her heart inclines more kindly toward the young Presbyterian minister who, clad in black, and with a voluminous theological volume under his arm, regards the pleasantries of the stranger with such manifest mislikings - either this, or else she has been so well brought up that even a cavalier in a red cloak and with high London manners cannot melt her reserve. Who shall say? The ways of women are passing strange!

I confess to a sympathy for the poor Cavalier fellow, and wish that a good tight ship may be landing with sassafras-wood at some near-by port, and that he may thence get a safe passage back to England again, and into more congenial surroundings.

I need to dig up more on Miss Mhoon, who studied with Pyle for about five years and who Pyle must have considered one of his stronger pupils: in spring 1897 she and Bertha Corson Day spent two weeks working in his Wilmington studio; her work was shown in several exhibitions of the Pyle-directed School of Illustration; Pyle featured two of her pictures in his article, “A Small School of Art” (Harper’s Weekly, July 17, 1897); and in 1898 she was one of ten students awarded a scholarship to the first Summer School of Illustration at Chadd’s Ford. If what I’ve learned is accurate, Mhoon was born June 6, 1876, in Mississippi, and died January 2, 1962. She married Hugh McDowell Neely (1874-1925) in Philadelphia in 1906 and had at least one child, named Hugh (1907-1937). All three are buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

“St. Valentine’s Day in New England” by Anne Abercrombie Mhoon (1897)

ST. VALENTINE’S DAY

by Howard Pyle

St. Valentine’s Day in the old times possessed a popular significance that we of these degenerate days of filigree paper and printed rhymes can hardly appreciate. Popular tradition had it that the birds mated upon the good bishop’s natal day, apropos of which Old Drayton, in Shakespeare’s time, writing a verse to his “Valentine,” begins his pastoral thus:

“Muse, bid the morn awake;and so forth, to his mistress’s eyes, lips, and other charms.

Sad winter now declines;

Each bird doth choose a mate;

This day's St. Valentine’s” -

Following these supposed habits of the feathered creatures, it became by-and-by a custom in the generation or so following for the men and women of that day to choose each his or her Valentine, to whom he or she was supposed to remain mated for the rest of the year. The gentleman generally entered into the compact with a poetic effusion and a gift, of more or less value, to the lady of his choice, and for the twelvemonth following he was supposed to devote himself exclusively to his chosen mate.

Usually the element of accident entered not a little into the choosing of the Valentine, for the first man and the first woman who met in the morning were supposed to remain Valentines and mated for the year to follow.

As witness to this, Gay, writing early in the eighteenth century, and beginning with the same theme that inspired Old Drayton -

“Last Valentine, the day when birds of kindsays,

Their paramours, with mutual chirpings, find” -

“The first I spied - and the first swain we seeOld Pepys in his immortal Diary - that great reservoir of dead and bygone gossip - gives us a number of glimpses into the Valentine’s day of his time.

In spite of Fortune shall or true love be.”

Once, mounting to the Olympian altitude of the gossip of White Hall, he tells us, apropos of Miss Stuart (afterward Duchess of Richmond), that “The Duke of York being her Valentine, did give her a jewel of about £800; and my Lord Mandeville, her Valentine this year, a ring of about £300.” Descending thence to the platitudes of his own private affairs, the good gentleman tells us very soberly that “I am also this year my wife’s Valentine, and it will cost me £5”; and adds, naïvely, “but that I must have laid out if we had not been Valentines.”

In another entry in his Journal he tells us how his wife hid her eyes lest she should see the masons working about the house, and so should miss choosing her proper Valentine; and in another place he informs us that “My wife, hearing Mr. Moore’s voice in my dressing-chamber, got herself ready, and came down and challenged him for her Valentine.”

From all of which we of these days may catch a certain remote notion of the importance of St. Valentine’s day in those far-distant old times so long passed away and gone.

As illustrating the importance of this one-time notable feast-day, Miss Mhoon has given a pictured image of the transplantation of the custom of the time into Puritan New England of, say, the year 1655.

We know what strong testimony the Puritans bore against the puddings and the “meat pies” (probably the mince pie of our day), and all the jocularities of the old Christmas season, and we also know that they made a point of studiously ignoring the anniversary of the King’s birthday. It is altogether likely they would look with even less favor upon the suggestive levities of Valentine’s day.

The somewhat seedy Cavalier, who is doubtless offering the Puritan maiden an effusion in these, in which dove is made to rhyme with love, and eyes with skies, and dart with heart, has perhaps been spending the whole long winter in the dull, cold little settlement for the sake of escaping, let us say, from the pressure of his debts at home. One can imagine how greatly a man of his parts must have wasted in such surroundings as the picture indicates. As for the Puritan maiden, either her heart inclines more kindly toward the young Presbyterian minister who, clad in black, and with a voluminous theological volume under his arm, regards the pleasantries of the stranger with such manifest mislikings - either this, or else she has been so well brought up that even a cavalier in a red cloak and with high London manners cannot melt her reserve. Who shall say? The ways of women are passing strange!

I confess to a sympathy for the poor Cavalier fellow, and wish that a good tight ship may be landing with sassafras-wood at some near-by port, and that he may thence get a safe passage back to England again, and into more congenial surroundings.

Valentine's Day, 1898

In the spring of 1896 the Pyle family moved from Ambassador Bayard's mansion - which was much too costly to maintain - to a more modest brick house at 1601 Broom Street, on the corner of Gilpin Avenue in Wilmington. Almost immediately, Pyle's daughter Phoebe found a best friend in Gertrude Brincklé, who lived next door.

Here we see Gertrude, grinning, next to Phoebe, whose face is obscured by her brother Ted. This detail is from a snapshot taken by Howard Pyle himself, apparently, during a children's party at his studio, about 1897. Pyle later used the photo as reference when painting the title page illustration for an edition of Hawthorne's The Wonder Book.

On Valentine's Day 1898 - "That was the year we had a big storm, with snow up to the hairpin fence," remembered Gertrude - Pyle presented his young neighbor (and future secretary) with an illustrated poem, which was later destroyed in a fire. The Broom Street house is one of the few Pyle homes that still stands, but the hairpin fence is gone, though I recall seeing remnants of it 15 years or so ago.

Here we see Gertrude, grinning, next to Phoebe, whose face is obscured by her brother Ted. This detail is from a snapshot taken by Howard Pyle himself, apparently, during a children's party at his studio, about 1897. Pyle later used the photo as reference when painting the title page illustration for an edition of Hawthorne's The Wonder Book.

On Valentine's Day 1898 - "That was the year we had a big storm, with snow up to the hairpin fence," remembered Gertrude - Pyle presented his young neighbor (and future secretary) with an illustrated poem, which was later destroyed in a fire. The Broom Street house is one of the few Pyle homes that still stands, but the hairpin fence is gone, though I recall seeing remnants of it 15 years or so ago.

A Soldier of Saint Valentine

In silk and golden lace

Was walking down Broom Street one day,

And there he saw thy face.

He thought it was the fairest face

The ever he had found;

He heaved a sigh, and gave one look.

And straightway he did swound.

Since then he mopes and pines with love,

His every breath a sigh;

He fain would be thy Valentine,

To ask he is too shy.

So here I send his pictured face

That you his love might know;

Unless he's buried in a drift

And lost beneath the snow.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

February 11, 1895

"Howard Pyle, the artist, has a very pleasant studio at his home in Wilmington, Del. While he is painting his pictures he dictates his stories to a stenographer. He is an enthusiastic musician and sings a good tenor."

Elmira Daily Gazette and Free Press (Elmira, New York), February 11, 1895

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

February 10, 1895

"But to revert to the weather - for we cannot talk of anything without reverting back to it - I don’t think I have told you how all the trains have been stopped on our local Rail Roads by the drifts. I myself returning from my lecture at the Drexel Institute yesterday, did not get home until nearly midnight. As it was, the cab collapsed in a snow-drift in front of Bush’s and I had to wade out and help the man with his horse."

Howard Pyle to Thomas Francis Bayard, February 10, 1895. At this time, the Pyles were occupying "Delamore," a mansion at the corner of Clayton and Maple Streets in Wilmington, while Bayard (the owner) was serving as the Cleveland Administration's Ambassador to the Court of Saint James.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

February 9, 1889

"Howard Pyle and wife started to-day for an extended trip to the Bahama Islands, to gather the information necessary for an article on the buccaneers of the Spanish Main, which he has engaged to write for Harper’s Monthly. He will stop at Jamaica en route."

Every Evening (Wilmington, Delaware). February 9, 1889

Sunday, February 7, 2010

A Howard Pyle Model

“Lola” by Howard Pyle (1908)

In 1925, Estelle Taylor, Hollywood actress and wife of world heavyweight champion boxer Jack Dempsey, reminisced in a syndicated interview about growing up in Wilmington. Here (from The Delmarva Star, February 7, 1926) she tells of what happened after she dropped out of high school:

Ida Estelle Taylor was born May 20, 1894, in Wilmington. Some biographies erroneously say she was born “Estelle Boylan” and was of “working-class Irish” stock, but she appears on the 1900 Census, aged six, the daughter of Harvey (or Henry) D. Taylor, a building and loan agent, living on a respectable stretch of Washington Street (just a few blocks north of Pyle’s home from 1881 to 1893). While she may have been of Irish descent, her parents and four grandparents were born in Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Estelle’s mother married Harry Boylan c.1913 - hence the Boylan confusion - but by then Estelle was married to Kenneth Peacock. She later moved to New York City and Hollywood and married Jack Dempsey in 1925.

Estelle vaguely says she dropped out in the “second grade” of high school. Gertrude Brincklé said Estelle posed for the title character of the story “Lola” for the January 1909 Harper's Monthly Magazine, which would have made her only 14 - a little young, but not out of the question. And Pyle was indeed at work on “Marooned” in 1908: he showed it in progress to his students Gayle Hoskins and Ethel Pennewill Brown on February 6 of that year.

Brincklé also recalled that Estelle first modeled for Clifford Ashley, who recommended her to Pyle, and that she went by trolley to the Taylor house to “hire” Estelle and escort her back to 1305 Franklin Street. Although Estelle does not mention Ashley in her interview, she does remember posing for Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, E. Roscoe Shrader, Stanley Arthurs, Charles MacLellan, W. H. D. Koerner, and Douglas Duer - all Pyle disciples. And she notes, “Altogether I worked for Wilmington artists for approximately two years.”

In 1925, Estelle Taylor, Hollywood actress and wife of world heavyweight champion boxer Jack Dempsey, reminisced in a syndicated interview about growing up in Wilmington. Here (from The Delmarva Star, February 7, 1926) she tells of what happened after she dropped out of high school:

Shortly afterwards I met Howard Pyle, the noted Wilmington artist and illustrator, and he asked me to pose for him.

After much urging Grandmother [Ida Barrett] agreed that I might pose for Mr. Pyle. For, as she said: “He’s such a fine man, the association may be very pleasant for you, and besides, (and with her it was a very important ‘besides’) the experience may get those stage ideas out of your head.”

But as to that last, it worked just oppositely.

I’ll never forget the day I walked into Mr. Pyle’s studio. The first thing I saw was a picture of a pirate sitting in the sand, with a bandanna about his head - his brow wrinkled in thought.

As I studied the picture which, I think, is one of Mr. Pyle’s most famous works, I fell to wondering what was in the pirate’s mind. I wondered if his future was troubling him as much as mine was beginning to trouble me. For I found myself consumed with restless ambition. And I immediately began to figure how, by posing for Mr. Pyle, and possibly other Wilmington painters, (for there were three separate colonies of artists there) I could earn enough money to start on the stage.

While those thoughts were going through my head Mr. Pyle came into the room. Although, on our first meeting, he had struck me as large, he now seemed taller and bigger - and much more formidable. I felt somewhat awed by him. And I began to fear that my posing days might be limited to just that one, for I was not at all sure that Mr. Pyle would like me as a model.

But I had all my fears for nothing. He was kindness itself and I never saw anyone more patient or more considerate, only sometimes he’d forget how long he had been working and would keep me in one position until I felt I’d drop from fatigue. That, however, I knew, was the result of his concentration on his painting. For, when he realized how tired I must be, he’d say: “Oh, I’m so sorry, child, you must be worn out. Now take a nice long rest.”

All the time he painted he whistled, no tune in particular, as I noticed over and over again, but a sort of medley - and he always seemed happy and contented with life. My experience as a model for him was extremely happy.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born May 20, 1894, in Wilmington. Some biographies erroneously say she was born “Estelle Boylan” and was of “working-class Irish” stock, but she appears on the 1900 Census, aged six, the daughter of Harvey (or Henry) D. Taylor, a building and loan agent, living on a respectable stretch of Washington Street (just a few blocks north of Pyle’s home from 1881 to 1893). While she may have been of Irish descent, her parents and four grandparents were born in Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Estelle’s mother married Harry Boylan c.1913 - hence the Boylan confusion - but by then Estelle was married to Kenneth Peacock. She later moved to New York City and Hollywood and married Jack Dempsey in 1925.

Estelle vaguely says she dropped out in the “second grade” of high school. Gertrude Brincklé said Estelle posed for the title character of the story “Lola” for the January 1909 Harper's Monthly Magazine, which would have made her only 14 - a little young, but not out of the question. And Pyle was indeed at work on “Marooned” in 1908: he showed it in progress to his students Gayle Hoskins and Ethel Pennewill Brown on February 6 of that year.

Brincklé also recalled that Estelle first modeled for Clifford Ashley, who recommended her to Pyle, and that she went by trolley to the Taylor house to “hire” Estelle and escort her back to 1305 Franklin Street. Although Estelle does not mention Ashley in her interview, she does remember posing for Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, E. Roscoe Shrader, Stanley Arthurs, Charles MacLellan, W. H. D. Koerner, and Douglas Duer - all Pyle disciples. And she notes, “Altogether I worked for Wilmington artists for approximately two years.”

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

A Howard Pyle Doodle

On his blog, James Gurney brought up the topic of doodles - specifically "phone doodles" - and asked "Just curious: What sort of doodles do you do?"

So I started thinking about what kind of doodles Howard Pyle did. And although I can't show a doodle he made while on the phone (a drawing he made while waiting for a phone call does exist, however, but I haven't looked at it and don't know how doodly it is), here is a bona fide doodle he made on a bridge score. Unfortunately, that's all I know about it. Whether he made it before, during, or after all the tallying, I don't know. Or maybe he just doodled on a scrap of paper lying around his studio (where he hosted many a bridge game). His secretary Gertrude Brincklé preserved this fragment, so I assume it dates from sometime between 1904 and 1910. Funny, I tend to doodle evil clowns, too...

So I started thinking about what kind of doodles Howard Pyle did. And although I can't show a doodle he made while on the phone (a drawing he made while waiting for a phone call does exist, however, but I haven't looked at it and don't know how doodly it is), here is a bona fide doodle he made on a bridge score. Unfortunately, that's all I know about it. Whether he made it before, during, or after all the tallying, I don't know. Or maybe he just doodled on a scrap of paper lying around his studio (where he hosted many a bridge game). His secretary Gertrude Brincklé preserved this fragment, so I assume it dates from sometime between 1904 and 1910. Funny, I tend to doodle evil clowns, too...