“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”

“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”

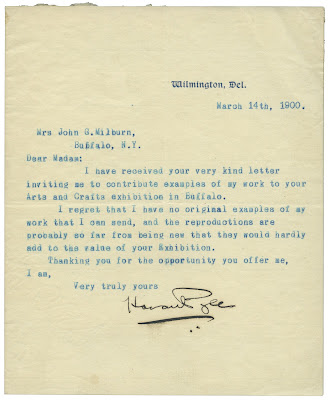

So wrote Pyle student Allen Tupper True to his mother on March 29, 1903. “His dinner” was Howard Pyle’s 50th birthday party, held at his Wilmington studio on March 5, 1903. There (as True had told his mother in a previous letter), in addition to the feast and festivities, Pyle had “made a good speech in which he told us of the organization he wanted among us and what hopes he had for the American Art that we were to build.”

“The committee on constitution has its work very nearly done now and we are all a bit proud of what we have done,” True wrote on April 12, 1903. “It is a hard business to get a hold of I find….” And a week later he said, “The work on the Constitution Comm. is about finished and our report will go before the crowd soon…”

The crowd, in this case, were the 18 official or “active members” of “The Howard Pyle School of Art”:

Stanley M. Arthurs

Clifford W. Ashley

William J. Aylward

Arthur E. Becher

Ernest J. Cross

Philip R. Goodwin

George M. Harding

Philip L. Hoyt

James E. McBurney

Gordon M. McCouch

Francis Newton

Thornton Oakley

Samuel M. Palmer

Henry J. Peck

Frank E. Schoonover

Harry E. Townsend

Allen T. True

N. C. Wyeth

(Absent from this list were several other Pyle students who had attended the birthday dinner, but who were not considered members of the school, per se, including Herman Pfeifer, Hermann C. Wall, Frank Bird Masters, and Ethel Franklin Betts. Also absent were Sarah S. Stilwell, Dorothy Warren, and Walter Whitehead, who had studied with Pyle after he resigned from the Drexel Institute. And it should be noted that although Pyle was always willing to critique the work of women artists who sought his advice, “The Howard Pyle School of Art” was strictly men only.)

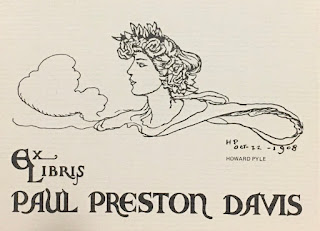

Eventually, the constitution and by-laws - as well as the text of the song sung at Pyle’s party - were handed over to Wilmington’s John M. Rogers, who was Pyle’s go-to printer for almost a decade. It’s not yet known how many copies were printed, but the copy seen here belonged to Henry J. Peck.

In his March 29, 1903 letter, True had said of the constitution: “It is a big serious business and unless I am mistaken, this organization - whose seeds only we are planting now - will be heard from in coming years and its influence will be decidedly felt in American Art of the future.”

But, as with many of Pyle’s big plans, “The Howard Pyle School of Art” - as a formal organization, at least - lasted only a few years before it fell by the wayside. Yet the Pyle “School” - in the broadest sense of the word - was indeed heard from and its influence was decidedly felt for decades to come.