“...the illustration for ‘Margaret of Cortona’ is now in the possession of Mrs. Dan Bates, to whom I gave it some years ago,” wrote Howard Pyle from his villa in Italy on August 10, 1911.

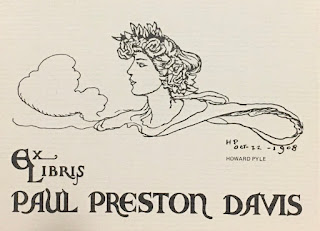

“Mrs. Dan Bates” was the former Bertha Corson Day (1875-1968), who was, as she herself put it, “an enthusiastic pupil of Howard Pyle” for several years, starting with his very first class at the Drexel Institute in 1894. In 1899 she attended the second Summer School of Illustration at Chadd’s Ford - where she was

photographed with the class on her 24th birthday. In May 1902, Miss Day married Wilmingtonian Daniel Moore Bates, Jr. (1876-1953) - already part of Pyle’s social circle - and when their daughter, Bertha, was born, Anne Poole Pyle presented her with a baby blanket she had quilted and which her husband had designed. (Incidentally, Bertha Bates - later Mrs. J. Marshall Cole, - is the only person I ever met who had known Pyle, if only slightly: she was just 6 years old when he sailed for Europe. Still...)

“Margaret of Cortona” was a poem (reprinted below) by

Edith Wharton, published in

Harper’s Monthly for November 1901, and - so far - this “collaboration” is the only known

solid link between them. They

did have several acquaintances in common, however, most notably Theodore Roosevelt and

William Crary Brownell of Charles Scribner’s Sons, who edited Pyle’s

The Garden Behind the Moon and several of Wharton’s works.

Wharton’s poem, by the way, (not Pyle’s illustration) was condemned by the Catholic press because of its depiction of the future

Saint.

Dominicana: A Magazine of Catholic Literature, for instance, said, “This poetic (?) blasphemy and historical slander is an evidence of extremely bad taste, because it offends against the canons of fact and truthful record.”

Harper’s Monthly even went so far as to print an

apology for publishing it.

Margaret of Cortona

by Edith Wharton

Fra Paolo, since they say the end is near,

And you of all men have the gentlest eyes,

Most like our father Francis; since you know

How I have toiled and prayed and scourged and striven,

Mothered the orphan, waked beside the sick,

Gone empty that mine enemy might eat,

Given bread for stones in famine years, and channelled

With vigilant knees the pavement of this cell,

Till I constrained the Christ upon the wall

To bend His thorn-crowned Head in mute forgiveness...

Three times He bowed it...(but the whole stands writ,

Sealed with the Bishop’s signet, as you know),

Once for each person of the Blessed Three -

A miracle that the whole town attests,

The very babes thrust forward for my blessing,

And either parish plotting for my bones—

Since this you know: sit near and bear with me.

I have lain here, these many empty days

I thought to pack with Credos and Hail Marys

So close that not a fear should force the door -

But still, between the blessed syllables

That taper up like blazing angel heads,

Praise over praise, to the Unutterable,

Strange questions clutch me, thrusting fiery arms,

As though, athwart the close-meshed litanies,

My dead should pluck at me from hell, with eyes

Alive in their obliterated faces!...

I have tried the saints’ names and our blessed Mother’s

Fra Paolo, I have tried them o’er and o’er,

And like a blade bent backward at first thrust

They yield and fail me—and the questions stay.

And so I thought, into some human heart,

Pure, and yet foot-worn with the tread of sin,

If only I might creep for sanctuary,

It might be that those eyes would let me rest...

Fra Paolo, listen. How should I forget

The day I saw him first? (You know the one.)

I had been laughing in the market-place

With others like me, I the youngest there,

Jostling about a pack of mountebanks

Like flies on carrion (I the youngest there!),

Till darkness fell; and while the other girls

Turned this way, that way, as perdition beckoned,

I, wondering what the night would bring, half hoping:

If not, this once, a child’s sleep in my garret,

At least enough to buy that two-pronged coral

The others covet ‘gainst the evil eye,

Since, after all, one sees that I’m the youngest -

So, muttering my litany to hell

(The only prayer I knew that was not Latin),

Felt on my arm a touch as kind as yours,

And heard a voice as kind as yours say “Come.”

I turned and went; and from that day I never

Looked on the face of any other man.

So much is known; so much effaced; the sin

Cast like a plague-struck body to the sea,

Deep, deep into the unfathomable pardon -

(The Head bowed thrice, as the whole town attests).

What more, then? To what purpose? Bear with me! -

It seems that he, a stranger in the place,

First noted me that afternoon and wondered:

How grew so white a bud in such black slime,

And why not mine the hand to pluck it out?

Why, so Christ deals with souls, you cry - what then?

Not so! Not so! When Christ, the heavenly gardener,

Plucks flowers for Paradise (do I not know?),

He snaps the stem above the root, and presses

The ransomed soul between two convent walls,

A lifeless blossom in the Book of Life.

But when my lover gathered me, he lifted

Stem, root and all - ay, and the clinging mud -

And set me on his sill to spread and bloom

After the common way, take sun and rain,

And make a patch of brightness for the street,

Though raised above rough fingers—so you make

A weed a flower, and others, passing, think:

“Next ditch I cross, I’ll lift a root from it,

And dress my window”...and the blessing spreads.

Well, so I grew, with every root and tendril

Grappling the secret anchorage of his love,

And so we loved each other till he died....

Ah, that black night he left me, that dead dawn

I found him lying in the woods, alive

To gasp my name out and his life-blood with it,

As though the murderer’s knife had probed for me

In his hacked breast and found me in each wound...

Well, it was there Christ came to me, you know,

And led me home—just as that other led me.

(Just as that other? Father, bear with me!)

My lover’s death, they tell me, saved my soul,

And I have lived to be a light to men.

And gather sinners to the knees of grace.

All this, you say, the Bishop’s signet covers.

But stay! Suppose my lover had not died?

(At last my question! Father, help me face it.)

I say: Suppose my lover had not died -

Think you I ever would have left him living,

Even to be Christ’s blessed Margaret?

- We lived in sin? Why, to the sin I died to

That other was as Paradise, when God

Walks there at eventide, the air pure gold,

And angels treading all the grass to flowers!

He was my Christ—he led me out of hell -

He died to save me (so your casuists say!) -

Could Christ do more? Your Christ out-pity mine?

Why, yours but let the sinner bathe His feet;

Mine raised her to the level of his heart...

And then Christ’s way is saving, as man’s way

Is squandering - and the devil take the shards!

But this man kept for sacramental use

The cup that once had slaked a passing thirst;

This man declared: “The same clay serves to model

A devil or a saint; the scribe may stain

The same fair parchment with obscenities,

Or gild with benedictions; nay,” he cried,

“Because a satyr feasted in this wood,

And fouled the grasses with carousing foot,

Shall not a hermit build his chapel here

And cleanse the echoes with his litanies?

The sodden grasses spring again - why not

The trampled soul? Is man less merciful

Than nature, good more fugitive than grass?”

And so - if, after all, he had not died,

And suddenly that door should know his hand,

And with that voice as kind as yours he said:

“Come, Margaret, forth into the sun again,

Back to the life we fashioned with our hands

Out of old sins and follies, fragments scorned

Of more ambitious builders, yet by Love,

The patient architect, so shaped and fitted

That not a crevice let the winter in - ”

Think you my bones would not arise and walk,

This bruised body (as once the bruised soul)

Turn from the wonders of the seventh heaven

As from the antics of the market-place?

If this could be (as I so oft have dreamed),

I, who have known both loves, divine and human,

Think you I would not leave this Christ for that?

- I rave, you say? You start from me, Fra Paolo?

Go, then; your going leaves me not alone.

I marvel, rather, that I feared the question,

Since, now I name it, it draws near to me

With such dear reassurance in its eyes,

And takes your place beside me...

Nay, I tell you,

Fra Paolo, I have cried on all the saints -

If this be devil’s prompting, let them drown it

In Alleluias! Yet not one replies.

And, for the Christ there—is He silent too?

Your Christ? Poor father; you that have but one,

And that one silent - how I pity you!

He will not answer? Will not help you cast

The devil out? But hangs there on the wall,

Blind wood and bone - ?

How if

I call on Him -

I, whom He talks with, as the town attests?

If ever prayer hath ravished me so high

That its wings failed and dropped me in Thy breast,

Christ, I adjure Thee! By that naked hour

Of innermost commixture, when my soul

Contained Thee as the paten holds the host,

Judge Thou alone between this priest and me;

Nay, rather, Lord, between my past and present,

Thy Margaret and that other’s - whose she is

By right of salvage - and whose call should follow!

Thine? Silent still. - Or his, who stooped to her,

And drew her to Thee by the bands of love?

Not Thine? Then his?

Ah, Christ—the thorn-crowned Head

Bends...bends again...down on your knees, Fra Paolo!

If his, then Thine!

Kneel, priest, for this is heaven...

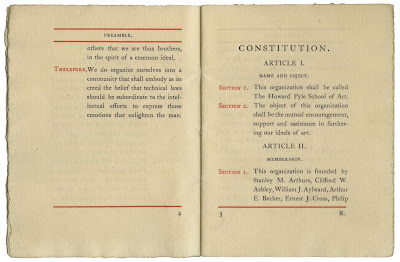

“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”

“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”