Howard Pyle photographed by J. R. Cummings in 1910

Howard Pyle photographed by J. R. Cummings in 1910

On his blog, James Gurney posted a reading he did from Henry Pitz’s

The Brandywine Tradition. Take a

listen.

In constructing that chapter, Pitz drew on the written and spoken reminiscences of several Pyle students. One of his main sources was an article published in the November 1919 issue of

Delaware Magazine, which remains, perhaps, the most extensive description of a Pyle “Composition Lecture”.

The author was an unsung and virtually unknown Pyle student named Elizabeth Keeler Gurney (any relation, James?). According to the 1900 Census, her parents were from Maine, but she was born in India in March 1881. She was a school teacher in Saint Cloud, Minnesota in 1900, and a little later began her studies at the Art Institute of Chicago. There, she may well have heard Pyle lecture in 1903 and 1905, and her schoolmates over the years included future Pyle students George DuBuis, Harvey Dunn, Edwin Roscoe Shrader, Helen Leonard, and Frances Rogers.

I don’t know when Miss Gurney came east to Wilmington, but

The Duluth News Tribune of September 2, 1907, had this to say:

ST. CLOUD YOUNG WOMAN SCORES SUCCESS IN EAST

----

Miss Bessie Guerney [sic], Artist Pupil of Howard Pyle, Now on Staff of Big Daily

Miss Bessie Guerney...a young artist of marked ability, is making an enviable record for herself under the instruction of Howard Pyle, one of the foremost artists in America. Though Mr. Pyle very seldom takes young women as students, friends of Miss Guerney succeeded in making her an exception with the artist, and after seeing some of her work she was instructed to “come on.”

It continued:

That she has made good is best evidenced by the fact that for several months past she has been a member of the staff of one of Delaware’s leading newspapers, dividing her time between studio and the newspaper.

I don’t know which newspaper she worked for, but I have an unsubstantiated hunch that she authored some Pyle-related articles that appeared in Wilmington’s

Every Evening in 1910 and 1911.

Since Gurney must have attended a good number of Pyle’s lectures, her 1919 reminiscence could very well be an embellished, composite portrait. But she alludes to “an article in a current magazine” - and

that turns out to have been

“An Artist Without a Pose” in the

Ladies’ Home Journal for March 1910. So I’ll give her the benefit of the doubt and say this particular lecture occurred in mid-February 1910, just after that issue of the

Journal appeared.

Later in 1910, just after Pyle sailed for Italy, Gurney gave a talk about him, his class, and his philosophy. When asked why he left, she said that he had “gone stale”. But her article shows Pyle at the height of his powers - and, perhaps, as he would have liked to be remembered.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AN EVENING WITH HOWARD PYLE

by Elizabeth Gurney

“Did you ever hear, and feel, and smell, as well as see a picture?”

This question was asked of his pupils by Howard Pyle, the famous Delaware artist, one winter night years ago. The class, together with invited guests had assembled in Mr. Pyle’s studio, on Franklin Street, in Wilmington, for the weekly evening lecture. Its members occupied a motley, yet beautiful, collection of colonial and mediaeval chairs - big chairs, little chairs, fat chairs, thin chairs - chairs as diversified as the Pied Piper’s rats. The chairs were drawn up in prayer-meeting fashion so as to face a long row of charcoal drawings, suspended like a family washing from a clothes-line. Flanking the line, painted canvases rested against convenient chair legs. Firelight played upon the polished hardwood of floor and walls, picked out shiny lights in queer jugs and bottles upon shelves; and illumined the eager, interested faces of the group of young women and men, mostly young men.

Carven ships’ figures, Venetian treasure chests, a piratical array of antique pistols and knives, bits of drapery, and easels, surrounded the group. Above them hung curious lanterns and many ropes ending in wooden balls. The ropes, when pulled, shifted skylight curtains; but how Mr. Pyle could ever tell what rope worked which curtain was a never-ending marvel to his pupils.

In the semi-darkness of an adjoining room some of the artist’s paintings could be dimly seen against the walls. Through gabled windows shone frosty, blue moonlight, accentuating the golden warmth within, and blackly silhouetting a few ivy leaves which had strayed across the windows from the mass thickly curtaining the outside brick walls.

Between pupils and drawings stood the tall figure of Mr. Pyle, massive of head. A pupil once remarked that with the addition of a powdered wig, Howard Pyle could have posed for a portrait of George Washington. The two men were not unlike in character. Great souled and kindly hearted, they possessed a personal dignity, even austerity, which did not unbend except in the presence of intimates. The artist’s pupils were greatly amused by an article in a current magazine describing the children of Wilmington as running up to Mr. Pyle, on the street to see what he had in his pockets! This Puritan dignity was marked in the artist’s paintings. His Spanish dancers were not sensuous; his oriental maidens were never voluptuous.

Mr. Pyle, his students, and his guests were surveying a sketch of salt marshes when he repeated his question.

“Do you consciously use all your senses to feel the reality, when composing or looking at a picture?” He made the class feel the dampness of the marshes upon their cheeks and the warmth of the sunshine; he made them hear the rustle of the breeze among the reeds, the songs of unseen birds, the lowing of invisible cattle; he made them fill their nostrils with the salt fragrance of the marshland; its brine was upon their lips. When he had finished, the class were not looking at a drawing, but were exploring vast stretches of moor with illimitable sky overhead.

“That is the value of pictures to make us feel life and truth!” he exclaimed. “Respect the truth,” was his most frequent admonition. He taught that an artist must have reality, not a picture, in his mind, when he put brush to canvas. He must mentally see real mountains in all their bigness if he would paint a picture that would make the beholder feel the grandeur of mountains. When the artist’s mind began to see a small painting of mountains instead of real mountains, when he began to think about his paints, or his technic, or himself, at that moment his work became artificial and without value, in the opinion of Howard Pyle.

“When I was painting

this picture of a battle,” he told the class, referring to a Civil War scene now in the State Capitol of Minnesota, “I felt the reality so vividly that I had occasionally to go to the door of the studio and breathe fresh air to clear my lungs of the powder and smoke.”

Mr. Pyle passed down the line of compositions, commenting vigorously.

“These are not real trees - they are only paint. A bird could not fly through the foliage without getting tangled up in the paint. The moon could not possibly be as large when so high above the horizon, and it would not be that color at the time of year indicated by the painting. Here is a man in a blizzard. Why is there no snow on his shoulders? Why is he not huddled-up as a man would be in the cold? Here is a laborer, digging in a trench. His muscles are not straining under the effort. Although he has worked at this job for some time, his clothes are as clean and unwrinkled as if they just were new from the shop. In this colonial picture, you do not feel that these people’s clothes are their usual attire. They wear them as stiffly and the clothes are as little wrinkled as if these were people at a fancy dress ball.”

The speaker paused and surveyed his audience reproachfully.

“You all know better. Why do you put falsities into your pictures when you recognize them as such the moment I point them out? Simply because you don’t think. Anybody can learn to draw. It is ease to draw, but it is very difficult to think. You haven’t material with which to think because you are all blind. Most people are blind. They don’t really see what is around them. Mention some building they have seen a hundred times. They cannot give an accurate description of it from memory. Store your mind richly by cultivating your observation.”

Mr. Pyle pointed an eloquent finger at his pupils. “A blade of grass. When I said that, did you see anything more in your mind than a green spear of grass?”

That was exactly what the class had seen. They shifted about guiltily in the mediaeval chairs, which promptly retaliated by prodding them in the ribs with unexpected knobs and corners. Mediaeval chairs were never intended to be sat upon. Probably more than one war of the Middle Ages was due to the soreness of body and temper of some king who had been oblige to spend the morning upon a mediaeval throne while his more fortunate courtiers could stand. However, being artists, Mr. Pyle’s pupils loved to sit in the mediaeval chairs because of their beauty.

“You ought,” continued the master, “to see that grass-blade pearled with dewdrops, waving gently in the wind, and a little red lady-bug struggling up its length.”

Perhaps because most of the drawings were in black and white, Mr. Pyle’s attention was now attracted to a Biblical subject in full color. It depicted the angel descending to touch the pool, whereupon the first infirm person to be lowered into its waters would be healed.

“There is much of value in this composition,” remarked the lecturer, with an approving smile to the happy young woman who had painted it. “But I seem to feel too much darkness and discouragement about it. I feel that all these poor, sick people would be bathed in the glory of light and hope shed upon them by the great angel of their redemption.”

“Gosh!” forcibly, if not elegantly, exclaimed the young woman artist to a friend after the lecture, “I painted that composition for a class in my art school in Chicago. The teacher there said that the light and shade were not well balanced. He recommended more white paint for the upper right-hand portion. His criticism left me cold. I brought the picture tonight to see how his criticism would compare with Mr. Pyle’s. The two criticisms mean much the same thing as far as the paint is concerned, but Mr. Pyle’s criticism is the one that inspires me. I want to go right home and finish that picture tonight!”

Now came the event for which the class had been hoping and praying all evening. Mr. Pyle seized a piece of charcoal and began remodelling one of the compositions. He did not often do this. He said it was too hard to lose himself in a picture when hampered by the consciousness of other people around. Like a miracle the composition took on life, while the class held its breath and realized its rare good fortune in seeing creative genius at work. Not a pupil moved hand or foot lest the spell be broken and the artist drop his charcoal. Mentally, each member planned to hold up the owner of the composition on the way home, and steal it from him. However, Mr. Pyle smudged out his work after he had ceased drawing. This always happened, but the class invariably hoped that for once he might forget to do so. The master explained that if he left it, the pupil might copy him instead of developing his own expression. Mr. Pyle was ever anxious to preserve the originality of his students, warning them against becoming imitators of himself, or anybody else.

The last composition to be criticized was the work of a pupil already famous in the art world. Mr. Pyle usually criticized such pupils with much detail, but with a respect which showed the high esteem in which he held their work. The present sketch was an illustration to a detective story, a murder scene.

“In the first place, it is a mistake to show gruesome and horrible things plainly in a picture,” was the comment. “The mind is so repelled that it instinctively refuses further attention and thus defeats the purpose of the drawing. Then, suggestion is always more powerful than a direct telling. Here we have the dead man, the knife, and the murderer, unmistakably shown. There is no mystery, nothing to puzzle and intrigue the imagination, and we turn away. How much more powerful would be a mass of men crowding around a slightly-seen object. Then there is mystery. We want to know what happened and who did it.

“Pictures should suggest so many possibilities as to set the mind to thinking, and thus hold the attention. We have all seen wonderfully painted groups in art exhibits - perhaps a vase and a bit of drapery, marvelously executed. The artist may have spent weeks upon the painting, yet it has little interest. We turn away, saying, ‘Very clever, but in heaven’s name why did he paint it?’”

Howard Pyle’s chief abhorrences were artificiality and sentimentality - not sentiment - in pictures. He disliked the aged man gazing at the ghost of his girl-wife in the opposite chair. He loathed doll-like girl heads decorated with exaggerated flowers. He even once complained of a painted dancing-bear because it lacked individuality. It was well drawn, but it was just any bear in general, not a particular bear with well-defined likes and dislikes.

Art was for everybody, in Mr. Pyle’s opinion. He had no patience with art teachers who used grandiloquent, technical terms. He believed art was life and truth, and as such to be appreciated by everybody, and to be talked of in the simplest every-day language. With the line of drawings disposed of, he generally concluded his lecture with a little good advice.

“Young people, don’t get the idea that you have an artistic temperament which must be humored. Don’t believe you cannot do good work unless you feel in the mood for it. That is all nonsense. I frequently have to force myself to make a start in the morning; but after a short while I find I can work. Only hard and regular work will bring success.”

“I wonder if we know how lucky we are to have these lectures?” queried one pupil of another, as they went forth into the starlight, the snow crisply crunching under their feet.

“Probably we shall never realize what treasures of heart and soul, Howard Pyle has freely poured out upon us until we can no longer have the lectures. Then we shall look back and say that these were the happiest days of our lives,” answered his friend, quietly.

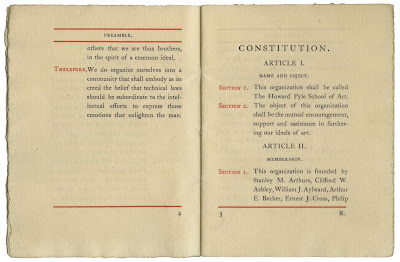

“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”

“The class organization that Mr. Pyle suggested at his dinner has been going forward and I am now serving as one of five on a committee for framing a constitution and perfecting some scheme for the school organization.”